Webshell Tradecraft in Monitored Networks

We've all done it at some point: upload a familiar webshell, get code execution and move on. In most lab environments, that approach works indefinitely because nothing is really watching. In monitored networks, however, file activity, process behavior, and HTTP traffic are continuously observed, and those same defaults can become obvious quite quickly.

This post looks at how webshell use changes once detection is part of the environment, and why assumptions formed in traditional labs tend to break down.

Webshells Outside of Unmonitored Labs

Often during offensive engagements, webshells are a mean to access a system or network remotely by compromising or modifying a web application. While code execution is the de-facto go-to in hacking labs, reaching your goals and keeping your webshell undetected is the main challenge while performing red team engagements.

File creation events, process launches, and HTTP request patterns are logged continuously, even when no alert fires immediately. The absence of an instant response doesn’t mean activity went unnoticed; it often means it was recorded, correlated, and queued for later analysis.

Where a file lands, how often it’s touched, what process executes it, etc. start to matter. From that point on, webshell tradecraft is less about the payload itself and more about how its behavior fits into the surrounding system.

File Drops, Write Paths, and What Gets Noticed

In most labs, any writable directory is fair game, and files can be dropped, overwritten, or renamed repeatedly without a defender starting to sweat. however, file creation/modification is one of the earliest and most reliable sources of visibility, especially in web-facing directories where changes are expected to be rare and controlled except for certain directories (uploads, logs, etc.).

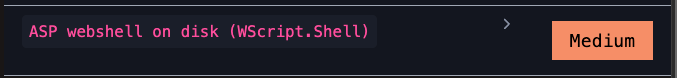

Unusual write locations, inconsistent naming, files that don’t resemble surrounding content, or sudden changes in otherwise static directories could stand out quickly. Moreover, most webshells use well-known execution patterns and helper functions to run commands, read output, or handle input such as eval() CreateObject("WScript.Shell") and child_process.exec(). This makes them easy to identify with host-based inspection using a simple signature.

A way to limit the exposure risk as a red teamer would be to avoid these code execution signatures and perform actions with language-specific functions available to you from within the webshell code. E.g. if you only need to read files on the system, instead of using: system($_GET['cmd'] . ' 2>&1'); and calling it with ?cmd=cat+index.php, you could use the builtin file_get_contents() or fopen() function and pass the file using an encrypted cookie value. The cookie in turn should be used/known by the application you are targeting.

The possibilities are often limitless as modern languages contain enough functionality to eg. run a full http to tcp socks proxy without even calling an external system program.

Process Chains Tell a Story

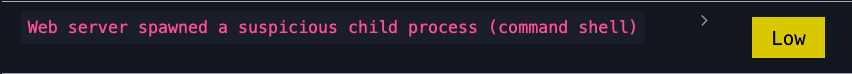

So now we got our webshell on disk, what's next ? cmd.exe /C whoami ? Web servers spawning interpreters or shell processes is not inherently malicious, but it is closely scrutinized.

There are multiple things that contribute to how activity is interpreted such as: the parent-child relationship, execution timing, user context, frequency, .... Unexpected child processes, or execution chains that don’t align with the application’s normal behavior can quickly stand out during analysis.

Many default webshells also rely on synchronous execution models: receive request, execute command, return output. This creates a predictable rhythm in process creation and termination that is trivial to observe over time. Even without inspecting arguments or output, defenders can correlate request timing with process activity and infer remote interaction with high confidence.

cmd.exe from w3wp.exe (IIS)HTTP Traffic Needs To Blend In

Now that our disk and execution tradecraft are handled carefully, we still need to communicate the actions we want to perform via the webshell. ?cmd=id

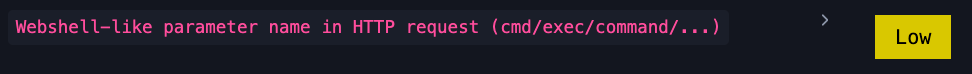

Common opsec mistakes include requests to the same endpoint, suspicious parameters and predictable request sizes. They create traffic patterns that are easy to baseline. When those patterns don’t align with how the application normally behaves, they become visible even without deep packet inspection.

Furthermore, the majority of public webshells have one or more of the following characteristics: fixed HTTP methods, suspicious parameter names, unusual request/response bodies, or command output returned directly in responses. They can all be flagged by lightweight inspection or application-layer logging.

As a red teamer, make sure that you hide (it being encryption or some other type of obfuscation) the command/action you want your webshell to perform. Common ways to achieve this are encrypted cookie values / HTTP headers or custom endpoints that are coupled to a certain action.

Tradecraft Only Matters Under Observation

The gap between “it worked” and “it went unnoticed” is where tradecraft lives. Training that removes visibility removes that gap entirely, and with it the opportunity to learn how real environments respond.

What matters is that as a red teamer, you are fully aware how your actions surface once they are observed, correlated, and reviewed over time. File placement, execution context, and HTTP behavior all leave traces that are easy to overlook in labs but more difficult to hide in real networks.

Written by the TraceHunt team as part of our effort to bring more realistic, OPSEC-aware training to the community.